Athena

Goal

How do we see? What brain mechanisms underlie our conscious visual perception of the world? This is a question that still largely eludes neuroscience. However, data science and machine learning applied to human brain activity have already revealed very interesting clues. I was part of the first wave of neuroscientists pioneering this approach using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging or fMRI, a technique that record brain activity in human using MRI scanners. Specifically, I created classification and reconstruction ML algorithms, specifically on the distribution of neural activity in humans observing certain visual stimuli. This resulted in four main publications in a leading scientific journal.

Figure 1 - The famous dress

Figure 2 - The Rotating Figurine

Ambiguous Motion and Depth Perception

Remember the dress in the image above? The one that some described as gold, and others as blue? Well, have a look at the figurine in Figure 2. Does it rotate clockwise or counterclockwise? Show it to a few colleagues or friends. Do they see the same? It's very likely some of them will disagree with you. This is the motion equivalent of the dress. But it is actually more interesting. Because with a little practice (some blinking helps), you yourself can make it move the opposite direction of how you first perceived it. And back again.

Consciousness

Since the thing you see doesn't actually change, but your conscious perception does, these type of visual illusions are ideal for studying perception. Imagine you are looking at what happens in a human brain when the see such an illusion. The image on the screen does the same thing over and over again. So, the brain activity it produces should be too, correct? But you seem to change your mind from time to time about what you perceive. Finding a pattern of brain activity that correlates with that 'change of mind' can thus be said to be related to your conscious perception of the world. Neuroscientists call this a Neural Correlate of Consciousness and they provide important clues about how you and I magically seem to experience the world. The rich phenological experience of 'being here'.

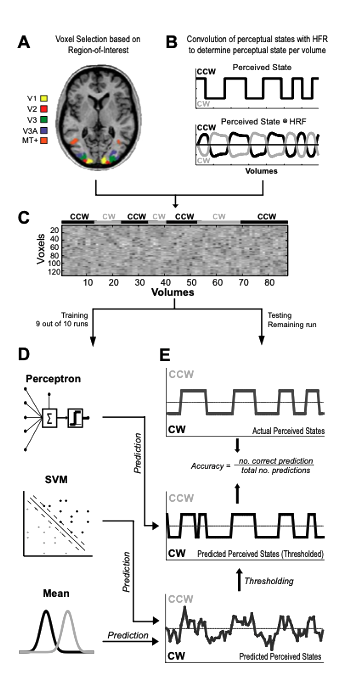

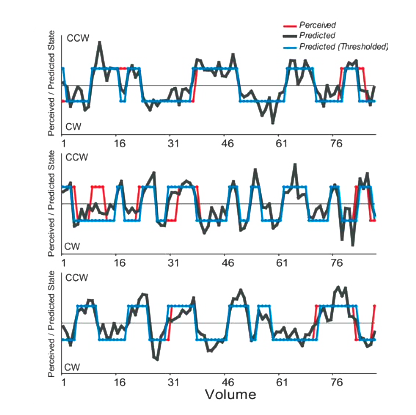

Figure 3 - Perception prediction pipeline

Machine Learning applied to human brain activity

And that is where machine learning comes in. In my first study, I placed human subjects inside an MRI scanner and recorded their brain activity while they watched a very similar visual, clicking a button when they perceived it to change rotation direction. Again, most importantly, it never did. It does not have a rotation direction strictly speaking. I t is all 'in the mind' of human in the scanner. After the brain scans were collected, I trained a number of different machine learning algorithms to predict what direction the human was perceiving over time. Then, I looked for patterns in the brain that created high accuracy when a validation set of brain scans was used. The logic being that any area of the brain that produces activity that a machine learning algorithm can use to predict over time what a person is perceiving is at least correlated with conscious perception.

Results

I did find these areas, but more importantly I by finding these areas I demonstrated you can use ML to mind read. That is to predict what a human is actually perceiving, from brain scans alone. I repeated the experiment with a different type of illusion, one based on depth perception (our sense of how far objects are from us and how big they are), resulting in a similar finding. My findings were published in a leading academic journal and kickstarted a whole movement of similar studies, with ever more sophisticated ML algorithms.

Figure 4 - Actual Perceived and Predicted Rotation Direction. Remember that the perceived rotation direction here was derived directly from brain activity

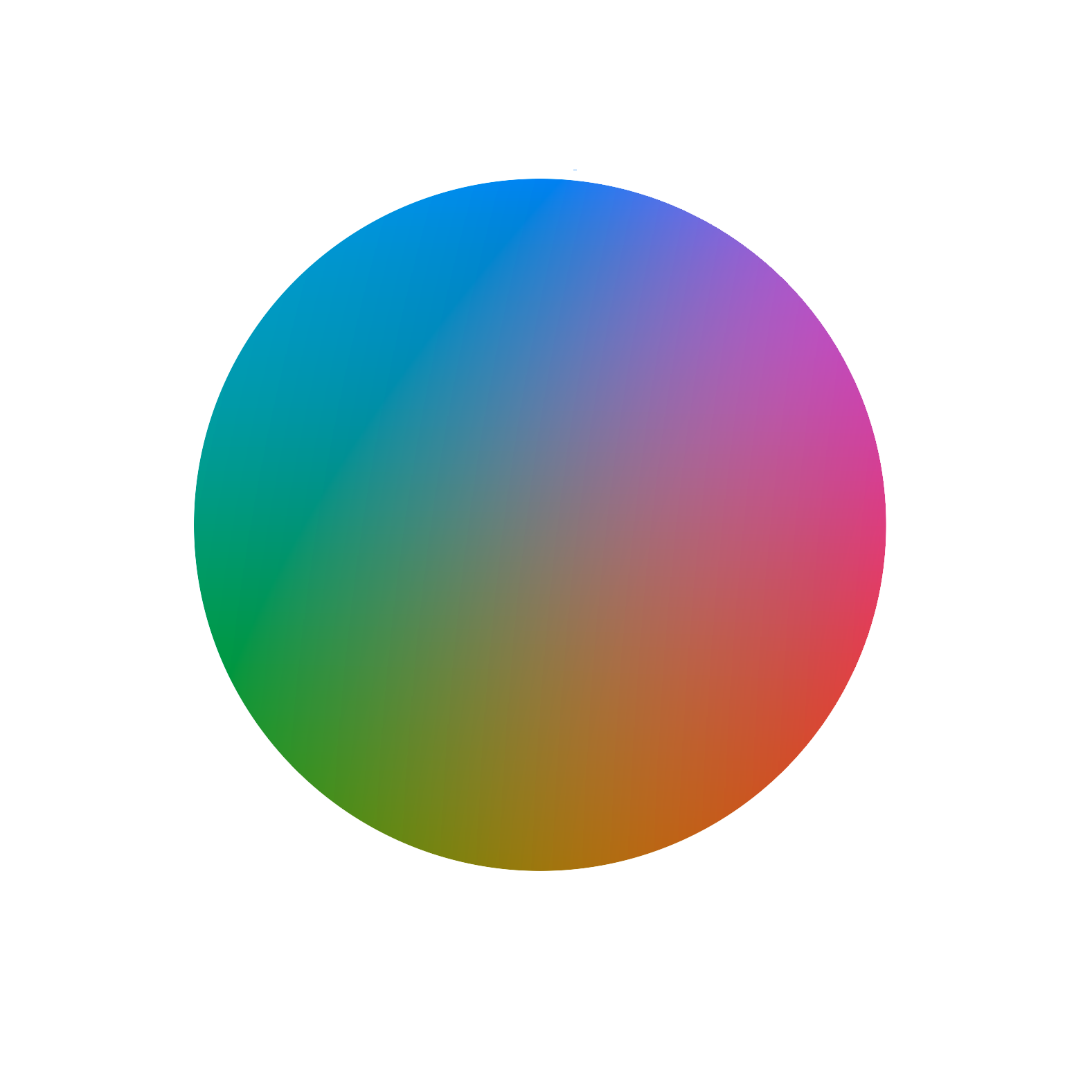

Figure 5 - The Color Wheel, representing the continuous space of perceived color. Here we see different hues (represented by the angle), at varying levels of saturation (distance from center), for a specific Lightness. However, within this continuous space, humans are quick to draw boundaries where one color category or term (i.e. red, green, purple) ends and another begins.

Reconstructing Color Perception

My early applications of ML to brain activity were all classification based. A ML classification algorithm can only predict the things it has learned. If you train an algorithm to recognize cats and dogs, it is not going to know what an iguana is. But what if you could design an algorithm that is generative: it recreates what somebody is perceiving. Imagine what you could do which such an algorithm! You could look inside somebody's mind!

Impact

Well, that is exactly what I managed to do. I used color perception because it is a relatively simple type of visual input. Brain imaging is limited in what it can do, especially when I conducted these studies. While we scanned subjects brains, we showed them a few primary colors, plus a few that are not (turquoise, pink, yellow). Then, I designed a novel machine learning algorithm and trained it on the brain activity produced by the primary colors so that a particular pattern of brain activity would be rendered on a computer screen as those same primary colors. After training, I applied it to the brain activity of non-primary colors the algorithm has never seen (not been trained on). Lo and behold, the output, rendered to screen matched the non-primary color!

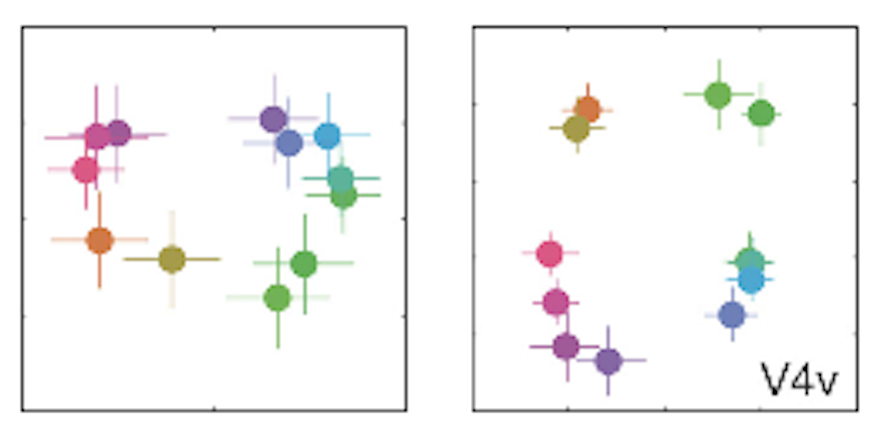

Figure 6 - Comparison between the neural representation of color during a diverted task (left) and attending to the colors themselves (right). Notice that attending to the colors groups them acccoding to their color category. The inset V4v refers to a particular brain area known to be selective to colors.

Applying Clustering Algorithms to brain scans

Have a look at this color wheel above. It varies continuously in hue and saturation Yet, depending on where you are from, you automatically divide it into color categories. Areas are green, cyan, blue, magenta, red, orange, and yellow. In other words, we group things that are actually different into the same category. I asked myself the question whether I could use unsupervised clustering algorithms to look for areas in the brain supported these categories. I showed human a series of different colors, equally spaced on the color wheel, while I recorded their brain activity. Then I applied a clustering algorithm to the resulting brain scans. If the clustering algorithm performs poorly on a certain brain area, the representation is probably continuous because there are no clusters to be found., if on the other hand they perform well and the clustering matches color categories, we have found a brain area that represents color in terms of categories.

Interestingly, what I found is that the brain can switch between the two modes. If the human being scanned were not paying attention to the colors but are instead doing some other task, I found no clusters. But as soon as the human in the scanner were asked to attend to the colors, the representation became categorical.

Technologies Used